- Home

- Miller, Miranda;

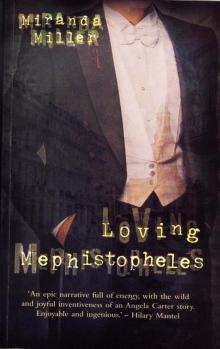

Loving Mephistopeles

Loving Mephistopeles Read online

When Jenny, a pretty but third-rate music-hall chanteuse in Edwardian London, remarks to her mentor and lover Leo, known also as the Great Pantoffsky, that she never wants to grow old she has no idea who he is. But her contract to love him will reside at the Metaphysical Bank in High Street Kensington for ever.

As Leo gleefully exploits the rich offerings of twentieth-century Europe – as a magician, fighter pilot, cocaine dealer and city banker – Jenny finds that the joys of eternal youth are more ambiguous than one might think. With the strain of constantly having to reinvent herself as her own offspring and watching friends, lovers and family live out their natural lives, she begins to regret her decision to sell her soul for immortality. But it is only when she becomes pregnant with a daughter that Leo’s true nature and that of her pact with him are finally revealed …

A compelling and fantastic journey in time and space, Miranda Miller’s ingenious reworking of the Faustian legend is by turns humorous, erotic and terrifying.

‘Miller’s intricate fictions are lit by the dark flicker of a strong and original imagination.’ – Hilary Mantel

MIRANDA MILLER was born in London in 1950 and has lived in Italy, Japan, Libya and Saudi Arabia. She has published six novels to date – including Loving Mephistopheles and Nina in Utopia (both published by Peter Owen) – a book of short stories about Saudi Arabia, A Thousand and One Coffee Mornings (Peter Owen), and a work of non-fiction that examines the effects of homelessness on women. She now lives in north London with her second husband, a musician, and is a Royal Literary Fund Fellow at the Courtauld Institute.

www.mirandamiller.info

Praise for Loving Mephistopheles

‘A wonderfully generous novel, several books wrapped into one, and I would have been very happy to stay with any of the strands or in any of the places it takes us to – I was particularly struck by the recreations of Edwardian London and of the London of the modern homeless. It’s an epic narrative full of energy, with the wild and joyful inventiveness of an Angela Carter story. It is enjoyable and ingenious, and I hope it will find many readers.’ – Hilary Mantel

‘The legendary pact always allures. I much enjoyed this spirited mingling of familiar wars, poverty, celebrity glitter with unearthly mischief, cynicism and self-transformations … Oddly angled history is laced with fantasy now strange, now macabre; surely an imaginative feat of storytelling.’

– Peter Vansittart

‘A brilliantly ambitious novel unlike any other; a London we recognize both lives and breathes amusingly and painfully … an absorbing read.’

– Lyndall Gordon

‘A truly remarkable novel, I read it with fascination’ – John Bayley

Contents

Part 1: Jenny and Leo

Jenny Mankowitz

Leo

Jenny Manette

The Bargain

Eugenie

Virginia

Leo’s War

Rapallo

London

George

Lizzie

Molly

On the Make

The Metaphysical Bank

Beautiful People

Femunculus

1983

Leo in Love

Doors Open

A Modest Proposal

David

The Contract

A Child Is Given

More Accidents

Feelings

Leaving

Midnight

Part 2: Abbie in the Underworld

The Sandringham

Leo and David

The House in Phillimore Gardens

Sibyl

Down the Plughole

Lunch

Mothers

Lost Children

Time Bites

Abbie in Love

In the Bunker

Flashback

Part 3: An Island in the Moon

2075

Organicists

Down to Earth

Genetic Love

I would like to thank the following people, whose encouragement and advice while I was writing this novel were invaluable: John Bayley, Martin Goodman, Lyndall Gordon, Bill Hamilton, Tim Hyman, Rebecca Miller, Antonia Owen, Judith Ravenscroft and Leslie Wilson. I am also indebted to the following texts: Dr Faustus by Christopher Marlowe, Howard Brenton’s translation of Goethe’s Faust Parts I and II; Europe’s Inner Demons by Norman Cohn, Marie Lloyd by Richard Baker and Max Beerbohm by N. John Hall. Hammer Horror films were also an important influence.

Prologue

‘Do you remember where we met?’

‘Down there, you mean? Hanoi, Hoxton, Hong Kong? All under water now, anyway.’

‘I’ve been trying to remember.’

‘Dangerous stuff, memory. Let me know if it hurts and we’ll cut out any malignancy.’

‘I thought I might keep it all. Write it down, even. Don’t you feel any nostalgia?’

‘You’re the only one I’d miss. And I have you. You’re not getting restless?’

‘No. I’ll stay up here now.’

For ever.

This conversation took place in bed. We still make love. Last week Leo’s penis dropped off, but we got him another one from the Metaphysical Bank.

Outside the window I watch our child playing among the fountains and unicorns and elves. Last year it was caves and vampires and dragons, but fairy-tales are very sentimental this season. Although this Abbie, of course, looks exactly like that other Abbie, she is more placid. I love her just as much but differently. Leo fusses over her absurdly. Neither of us can quite believe, even now, that there really are no dangers here.

Of course, those of us who are eternally young and rich have always hovered just above the earth, as if in balloons, observing with curiosity and, sometimes, compassion. Now that science has caught up with science fiction we have cut the ropes, and here on Luna Minor the earth is the stuff of nightmares. After a good dinner we exclaim with horror and raise our eyebrows at the latest catalogue of disasters down there: meteors, earthquakes, floods, famine, drought. Such a masochistic planet, you’d think those one-lifers would make the best of what little time they have instead of wallowing in misery. We send down ships full of food and old clothes but no longer go ourselves. Not after the last time.

Yet the London of my imagination still has great power. If I was properly old I suppose I’d be forgetting it all. Now, instead of dementia I experience a kind of volcanic recall; memories erupt so intensely that I can hardly believe those events happened so long ago. They’re still scalding hot, their power undiminished. Imagine what it’s like for Leo who’s been around for centuries. He never wants to talk about the past.

‘What are you thinking?’ he asks with that anxious note in his voice that still surprises me. Once, he would have known but wouldn’t have cared.

‘I was thinking about – our daughter.’ I usually avoid referring to her as Abbie.

‘She’s so talented and inventive, a wonderful child. Perhaps you were right to insist on all that revolting blood and slime. I’m sure the computer-generated children aren’t so original.’

‘For her birthday she wants to orchestrate the meteors.’

‘Why not? My little Mozart!’ You’d think he’d always adored children and been the most indulgent of fathers.

Now that she is nearly eleven it all comes flowing back. Three little girls triplicated in time and space. At the same age that other Abbie had to struggle with poverty and I was blind and couldn’t help her; a century before that I was a child myself, not that childhood was much gushed over in Hoxton at the beginning of the twentieth century.

My past is a film I play back to myself each night as I lie

beside Leo. Pictures, colours, arbitrary memories – I’ve been telling my story to myself in grand operatic events: love and death and vicissitudes of fortune. But it’s the ordinary moments that my memory savours and replays to me now, refusing to accept my own judgement of what was important. Those moments are so intense that they draw me into a perpetual present, a river that carries me back to London. My city resurrects itself and so do the people, who will live for as long as I refuse to forget them.

Two hundred years ago, ten seconds ago.

PART 1

Jenny and Leo

Jenny Mankowitz

My mother and father sit together over my sister Lizzie’s cradle. A rare moment of intimacy in their mutual destruction, which usually leaves Ma alone with two little girls in small, bare rooms while our father goes out drinking. But this is an image of tenderness, the two beautiful faces leaning over the wooden crib. My father is a classically handsome Jew, tall and slim with curly black hair, huge dark eyes, olive skin and a long harmonious face. My mother is also tall, with wavy light-brown hair swept up in a magnificent Edwardian chignon, creamy skin, green eyes and a bustle of vitality and purpose that make her thrilling to watch.

I’m not in the picture, of course, because I’m holding the camera of memory, filtering their long-dead faces through the merciless eyes of a jealous three-year-old. This is the first time I’ve thought of my parents as lovers, as a sexual couple. Lizzie and I must have been conceived in passion.

Quarrels and sulks as the handsome, feckless couple sink into debt. My father has just enough determination to reject his Orthodox background but not enough to accept responsibility for his young family or decide whether he wants to be a musician or a tailor or a baker. My mother soon comes to despise his weakness more than she loves his charm and good looks.

A game I play with Lizzie on summer evenings in our back yard: we put blankets over a clothes-horse and sit cross-legged in the dark tent it makes, then dare each other to run into the kitchen and steal pans, plates, raw carrots and lumps of dough for ‘our house’. Ma hates domesticity, poverty, children and noise. I already know this, so I hide, disappear – as my mother will do herself a few years later when she sails off to Shangri-La via Jo’burg.

Under the dark blankets Lizzie and I inhale the stuffiness, the smell of old bodies and tea and bacon – for my father enjoyed flouting the taboos of his parents – and watch sunlight filtered in tiny needles. Our scabby knees and elbows touch as we whisper, giggle and squabble. We love it when the roof falls in, when the blankets collapse and tangle with our pots and food. Then we have to get up and rebuild our house, weighing the corners of the blankets with stones and crawling back through a flap. Inside, the rich darkness encloses us again, hugging us in our own thoughts, smells and dreams.

Two sisters in white night-dresses in bare rooms, dreaming and squabbling and kicking each other in the single bed we share every night. It’s so cold that the condensation freezes on the cracked window-pane and streams down the walls. Lizzie brushes her long black hair with the hairbrush we share and squabble over, splashing her face with cold water before jumping into bed to kick me.

Our parents must have married young. There’s a much older brother I can hardly remember, Spencer, a name associated with beautiful stamps and financial hopes. At fourteen he was sent off to South Africa to seek his fortune. I imagine him, a huge shadow wrapped in an envelope, sailing across the ocean with a bundle tied up in a handkerchief like Dick Whittington. Spencer has found his fortune, a warm shiny word. Ma and Pa have fallen from genteel heights, but Spencer’s fortune is going to lift them up again. The less money there is, the more my parents talk about it.

‘Looking for work and hoping to God he doesn’t find it,’ Ma says of my feckless father. Every few months we change rooms and schools. The rooms get smaller and the schools rougher. I know landlords are bastards, jobs are slavery, schools are pigsties, pubs are where the money goes, pawnbrokers cheat you and other children hit you if you don’t hit them first. Pa hates religion, all of it, Jewish or Christian. When he ran off with Ma – who was Jewish, too, but never went to synagogue – he fled from his family, who lived in a hebra in Bethnal Green with other families from the same shtetl in Poland. Although all he has fled to is more poverty, my father says he’s glad to have escaped from the Talmud. Won’t let us have anything to do with the missionaries who flock to save our degraded East End souls. I always want to go along and have tea and cake and sermons, but we aren’t allowed.

Sometimes the battle between Ma and Pa spreads. One night I look out of the window and see the whole street erupt into a fight – like a party, only with fists instead of buns. Softly illuminated, like dancers on the gas-lit cobbles, men and women punch and claw at each other. Through the cracked glass I see heads hit the cobblestones, noses squashed like tomatoes, a straw hat torn off with a clump of hair attached to it. Pa has left again, and behind me I hear Ma’s voice. ‘These people are scum; they don’t know any better. Don’t look at them, Jenny.’

Pa doesn’t happen any more. We move again, and Ma shares a bed with us, snoring and sobbing and smelling like Pa did when he came home. Lizzie and I think it’s wonderful to have her in bed with us; we don’t care how smelly and noisy she is.

Then Ma goes off to South Africa to be with Spencer, who we always knew was her favourite just because he was a boy. I’m twelve, three years older than Lizzie, and we go to live with Auntie Flo, who isn’t our aunt but some kind of relation. She’s quite kind really, but I can’t forgive her for not being my mother. I can see her street, the chandler’s and the beer shop and baker’s. Little brick houses with ‘Mangling done here’ signs in the windows. We think Auntie Flo’s rich because she has the whole house and doesn’t do mangling.

Auntie Flo’s crappery down at the end of the yard, frozen in winter and flyblown in summer, is so terrifying in the middle of the night that Lizzie and I refuse to use it and develop bladder infections. The chamber pot’s icy, too, and most nights it’s too cold to pee or do anything except huddle against Lizzie’s back in bed. We squabble over which side of the lumpy mattress to sleep on and who used the curling tongs and which one of us was to leave the breakfast tray for Mr Barnabus, the only one of Auntie Flo’s lodgers who isn’t downright hideous. Lizzie thinks it’s the end of the world when I kiss him.

Every morning my sister and I walk to the Bath Street School, where we don’t learn anything, but at least for two whole years we live in the same house and go to the same school. When I come home I search the table in the murky hall for the letter from Ma that never comes. I think my glamorous mother in South Africa is proud of me, misses me. I think she has only left us because she had to and because our big brother Spencer is going to make lots of money and send for us.

Only she doesn’t. The envelopes with beautiful stamps arrive every few months, but they’re not addressed to me or Lizzie. They’re for Auntie Flo, full of money to pay for our keep, so we must be worth something.

On my fourteenth birthday, when I have to leave school, my horizons barely fill the grimy window of the room I share with Lizzie. Auntie Flo takes in lodgers and sometimes works as a barmaid at the Falstaff. Ma didn’t work because she was a lady really. I can just about imagine working in the hat shop in Kingsland Road. I’d have to wear a black frock and stand rigidly to attention and call other women madam. A job like that would be posh, grand, swish, compared with the only alternatives, which are the baby-boot or feather-curling factories.

All I know is I hate babies and I want to be the one who wears the hats and the feathers. I know men stare at me, and there’s money in that. On the other side of London, where I’ve never been, there are theatres and carriages and jewellery that might as well be worn by me as by engravings in illustrated newspapers. I’ve been to music halls, and the only women I’ve ever heard of who did anything except have babies are Queen Victoria, Marie Lloyd and Vesta Tilley. If you can’t get a job as a queen you can always lea

rn to sing and dance. Auntie Flo says girls who go on the stage aren’t much good – although with a nod and a wink and a leer, implying that being good isn’t much fun.

Leo

‘Leopold M. Bishop, professional Tutor and Agent, prepares ladies for Theatres or Music Halls and procures Engagements. Easy payments. Stamped agreements given to every Pupil.’

Leo always did like contracts.

I’ve chosen him out of a list of men claiming to teach acting because his name is Bishop and I think bishops are safe. I go to see him, clutching his advertisement from the local paper and my only white gloves. I’m afraid they’ll get dirty if I wear them.

I’ve never seen these streets before. Bloomsbury. Huge white houses like slabs of blooming cake, the dark pavements shiny with rain. London still feels imperial and pleased with itself. These houses are full of objects and people that know their place. You can tell at once they don’t do mangling, they don’t even put their own clothes on or cook their own food. I can smell the rain, the sap in all these trees that aren’t allowed to grow in Hoxton and my lavender perfume that I saved up for weeks to buy. My heart gallops with terror as I approach his house.

A uniformed maid like a bossy penguin shows me into a comfortable overcrowded room. Behind a carved desk is a tall, thin man with brown hair and dark-blue eyes, well dressed. He looks about thirty, more than twice my age but not old; looks so like the dream lover I’ve been imagining since I was twelve that I at once feel naked, as if he’s been spying on my fantasies. I’m sure he knows my stays are too tight and my shoes and blouse and skirt are ridiculously big, borrowed from Auntie Flo. But I haven’t come all this way just to be sent packing, so I walk straight up to him and say, ‘I want you to teach me how to act. I want to be like Marie Lloyd.’

‘Nobody is like her. That is why she is a great performer.’

Clumsily I audition, and he agrees to teach me.

For a year I give him most of the money I earn curling feathers and sewing them on to hats, boas and evening cloaks. My fingers are sore, and I hate each slippery feather as if it’s a spiteful bird sneering at me. I’m determined that one day I’ll wear these garments I’m sewing for other, richer women. Twelve hours a day I sleep-walk at the factory, and for two hours a week, on Sunday evenings, I wake up. Leo teaches me how to walk, speak, read, act, sing, dance, dress and breathe.

Loving Mephistopeles

Loving Mephistopeles